By: Heather Joslyn

Nine … point … six … billion … dollars.

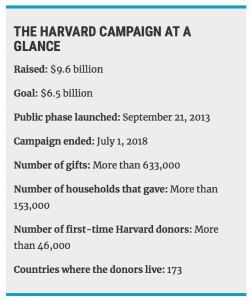

Fundraisers have been rolling that figure around in their heads in the wake of Harvard University’s announcement that its most recent campaign, which concluded July 1, brought in more money than any previous drive by any institution anywhere.

The One Harvard campaign, announced in 2013, originally sought $6.5 billion, which would have bested the record-setting $6.2 billion Stanford achieved in a campaign it ended in 2012. Harvard blew past Stanford’s mark in 2016.

The drive made America’s richest university, with a $37.1 billion endowment, even richer. But its success reveals new possibilities for other nonprofits running high-octane campaigns, say campaign leaders and experts.

“It’s kind of like breaking the four-minute mile,” says Trent Ricker, chief executive of Pursuant, a fundraising consulting company.

The breakthrough might spark a new phase of competition among America’s biggest universities, says David King, president of the fundraising consulting firm Alexander Haas.

“It would not surprise me in the not-too-distant future to see Stanford come out and say, We’re going to raise $12 billion,” King says. (A spokeswoman for Stanford said the university declined to comment.)

The campaign, the first to involve every school at Harvard, also served as a capstone to the careers of Drew Gilpin Faust, who retired as the university’s president on July 1, and Tamara Rogers, vice president for alumni affairs and development. Faust, still a history professor at Harvard, has been succeeded by Lawrence Bacow.

Rogers, who began her Harvard career in 1976, moving into development work in 1990, announced plans in January to step down. She will be succeeded in November by Brian Lee of the California Institute of Technology, which is in the midst of a $2 billion campaign of its own.

Susan Feagin, president of the consulting firm John Brown Limited and a former top fundraiser at Columbia University, served as campaign counsel.

Secrets of Success

The success of the One Harvard campaign came from a global fundraising push that made an aggressive effort to bring every part of the institution together in a search for new support,, Rogers says.

But some of the success was the result of something the university didn’t have control over. “The stock market was booming. I recommend that to everyone,” she says.

The university also hadn’t run a comprehensive campaign since one that ended in 1999 and raised $2.65 billion.

“In a funny way, there was almost pent-up demand,” Rogers says. “Volunteers certainly weren’t feeling exhausted or fatigued in any way.”

Among the other factors that led to success:

Engaged leadership. Faust, who assumed the Harvard presidency in 2007, was key to connecting with donors, Rogers says.

“We had a great president, and we had got her out from the very beginning so that she had the relationships, meeting the deans and presidents,” Rogers says. “We made sure that people met the academic leadership, so there was that level of trust.”

Digital-communication needs. “We didn’t labor over a case statement,” Rogers says. “That, in the end, didn’t really matter much. Many institutions are wondering about the value of case statements in a time when digital communications are very mutable and changeable as one goes along.”

An inclusive and decentralized structure. The campaign was the first to involve every school on campus.

“Every school had a goal. Each dean pitched in to figure out what was needed for that particular school and to identify priorities and donors in advance,” Rogers says. “We could include some of these people in the campaign executive committee and in other voluntary groups. It looked like a matrix of people involved in the campaign across the university.”

Every school met its campaign goal. Among the transformative gifts the campaign secured were a $350 million unrestricted donation in 2014 to the School of Public Health from the Morningside Foundation to rename the school in memory of the late T.H. Chan., a Hong Kong real-estate businessman, which Rogers calls “a surprise and a delight.” A $100 million pledge from David Rockefeller, made early in Faust’s tenure with the understanding that it would count in a subsequent campaign, was the drive’s first nine-figure contribution.

Smaller donations mattered, too. Near the end of the campaign, Rogers says, there was “a surge of giving for undergraduate scholarships and a lot of people encouraging each other to give. That was real momentum.”

A well-staffed development team. Harvard trimmed the size of its development staff after its endowment took a hit during the financial downturn. By the time the campaign’s public phase began, Rogers says, the staff ranks returned to pre-recession size, plus the university hired additional fundraisers to focus on gifts of $10 million or more and to solicit donations to benefit the entire university or projects that covered more than one school, such as stem-cell research or behavioral-economics scholarship.

In a hot job market, and a market full of big hospitals and colleges, attrition proved a constant challenge. “We lost people all along the way,” Rogers says.

Some of those who stayed at Harvard will probably get snapped up by other institutions now. “You tend to lose a lot of talent immediately after the close of a campaign,” says King, the consultant. “They all have this nice, shiny new thing to put on their résumés.”

Keeping the Harvard development staff relatively intact will soon be her successor’s challenge. But Rogers, who first moved into major-gifts fundraising from a position in Harvard’s admission office and worked as a recruiter in the 1990s, thinks casting the net wide when making new hires will help fill any gaps.

“Sometimes people in our field undervalue other experience,” she says. “Hiring people who come from admission, from finance, or consulting, from a range of different backgrounds, can be very, very successful. They can also bring new thinking, they can be imaginative. And so I strongly endorse that.”

A broad range of volunteers. Volunteers were essential, Rogers says, and the campaign found roles for many of them at all levels. More than 40 committees, staffed by more than 1,400 volunteers, helped drive the effort.

Each school’s campaign committee had at least one co-chair who was not an alumnus of that school and was not married to one, Rogers says. This helped create cross-campus interest from donors; most of the gifts of $10 million or more, she says, supported more than one school at the university. Ten percent of giving over all came from donors who weren’t Harvard alumni.

A strong international fundraising game. People from 173 countries donated to the campaign, reflecting the institution’s global profile. The university identified campaign volunteers in many countries and organized Your Harvard events for alumni across America and the world featuring panels of speakers and messages from Faust. The events were not explicitly fundraising but a way to make far-flung alumni feel connected to the university and alert them to the campaign. Also, “we have Harvard Clubs all over the world,” Rogers says, which run programs and sometimes help dispatch alumni to interview prospective students at the university’s behest when travel to the Massachusetts campus is not practical.

Rogers’s team also sought the advice of philanthropists in some nations where charitable giving is new. “We were able to bring in those philanthropists and discuss the campaign and take their advice about how to work in their setting in order to bring people close to Harvard.”

A Winning Strategy

The campaign affirms a strategic advantage for research universities, in particular, in making their case to donors, says Daniel Diermeier, provost of the University of Chicago, which is in the home stretch of a five-year campaign aimed at raising $5 billion. (The drive winds up in June, with $4.5 billion raised so far.) The $5 billion is a reach from the original goal of $4.5 billion.

Research universities generate society-changing discoveries and solutions, he says, and donors craving impact are responding to that case for support.

“You’re seeing this at Harvard, at a bunch of our peers, where they’re resetting their campaign goals,” Diermeier says. “If they’re giving to the University of Chicago, those gifts have the possibility to be transformational. You’re utilizing the entire capacity of the university for impact. Donors are increasingly realizing that.”

The University of Chicago’s campaign is called Inquiry and Impact. Other current campaigns framed similarly include:

- The MIT Campaign for a Better World, launched in May 2016 and aiming to raise $5 billion, reported $4.3 billion as of the end of its 2018 fiscal year.

- Rising to the Challenge: The Campaign for Johns Hopkins University has raised $5.87 billion. It has extended its original goal of $4.5 billion and also the length of the drive, now scheduled to end October 10, with more than 820 gifts of $1 million or more so far.

- The University of North Carolina’s For All Kind campaign, aiming for $4.25 billion by 2022, has already raised $2.23 billion. Forty-one percent of gifts have come from nonalumni.

For other organizations that are in or planning campaigns, Harvard’s example “just shows what is possible,” says John Hewko, general secretary of Rotary Foundation of Rotary International. The service organization, which works on eradicating polio worldwide, is seeking to raise $2.025 billion for its endowment by 2025.

“Harvard has a big alumni base. We have a big member base,” says Hewko, whose organization has 1.2 million members worldwide. “It encourages us.”

Audacious Inspiration

Whether Harvard’s record-breaking campaign will intensify the “arms race” among colleges for ever-higher fundraising goals remains to be seen, experts say.

Certainly grumbling about rich institutions getting richer is fair, Ricker says. But regardless of what happens next, he adds, “it should inspire nonprofits of all sizes — even if you’re about to go out with a $50 million vision campaign. We’ve known for a long time that there’s great generosity. I think we can all look at it and benefit from it.”

Not the least of the lessons is the boldness of Harvard’s faith in its donors. “The $6.5 billion goal is audacious enough,” Ricker says. “They didn’t know how they were going to do it. At some point, Faust just drew a line through it and said, ‘We’re gonna rock ’n’ roll.”

This article originally appeared in The Chronicle of Philanthropy.